So let’s get clear about text dependent questions (TDQs.) What does that have to do with close reading? Keep reading and you’ll soon find out.

Before you engage in dialogue about either, it is imperative that those in the conversation hold the same definitions. For example, last year I observed a professional developer inform teachers that close reading meant holding the text closely and reading slowly. Yes. She said that. If we engaged in dialogue we’d be using the same terms, but holding different definitions. We’d be talking, but we would not be communicating.

Such was the case for a district literacy leader that I coach. She was asked to model the Elder-Paul method of close reading–the method adhered to on this blog. Specifically, she was asked to demonstrate Level 1 using triad groups along with TDQs and that was the problem. To those who requested her demonstration, TDQs were simply questions related to the text; however, she embraced the meaning purported by the Aspen Institute (2012).

An effective text dependent question first and foremost embraces the key principle of close reading embedded in the CCSS ANCHOR READING STANDARDS by asking students to provide evidence from complex text and draw inferences based on what the text explicitly says (STANDARDS 1 AND 10) (p. 1). [The emphasis is mine.]

Now, you can choose to ask students to draw inferences after Level 1, but you’ll be sure to frustrate your students and possibly yourself because Level 1 is about paraphrasing the author’s thoughts. On this level, students are just beginning to gain an initial understanding of the complex text-the operative word being complex. This is not an ideal time for most TDQs as defined by The Aspen Institute. Furthermore, the institute suggests how to frame TDQs. The suggestions are listed below along with my recommendations for the appropriate levels of close reading. The questions should focus on the following:

- Defining academic vocabulary (Level 1-2)

- Testing comprehension of ideas and arguments (Levels 2-5)

- Unpacking challenging portions of the text (Levels 2-5)

- Why the author chose a particular word/phrase (Levels 3-5)

- Examining the impact of sentence structures (Levels 3-5)

- Tracking down patterns across sections of text (Levels 3-5)

- Looking for pivot points in the paragraph (Levels 4-5)

- Noticing what is missing or understated (Levels 4-5)

- Investigating beginnings and endings of texts (Levels 4-5)

*Note: defining vocabulary was a part of her lesson, but they wanted to see her model TDQs 2-9 while modeling close reading Level 1.

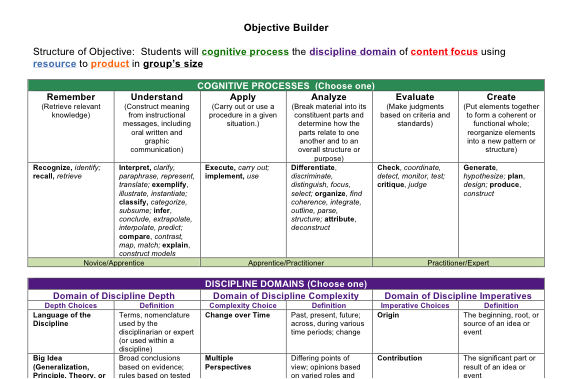

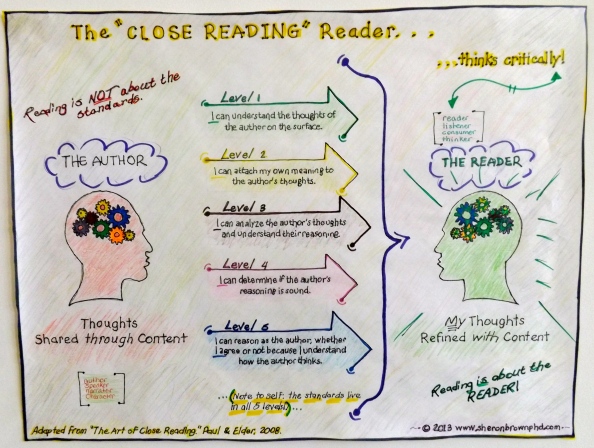

Most of the frames are best after Level 1 which only requires sentence level paraphrasing. Level 2 requires students to summarize the author’s thoughts and relate them to information they already know; Level 3 requires students to analyze the author’s thinking based on the eight elements of thought; Level 4 requires students to evaluate the author’s thinking based on the intellectual standards; and Level 5 requires students to integrate the author’s thoughts with his own and/or others’ ideas and concepts. (See this graphic for a visual explanation of the levels.)

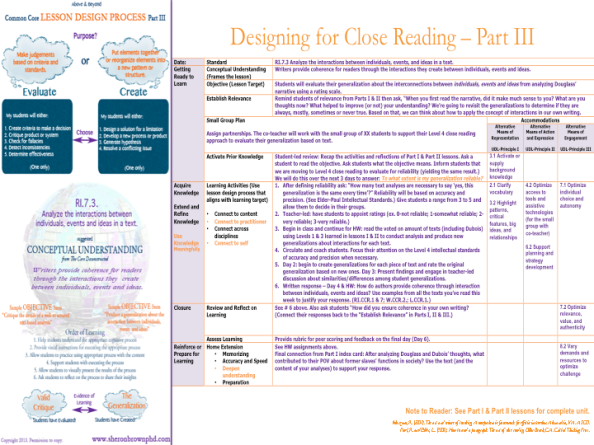

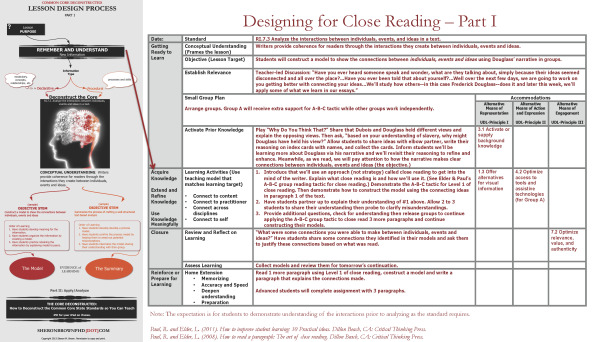

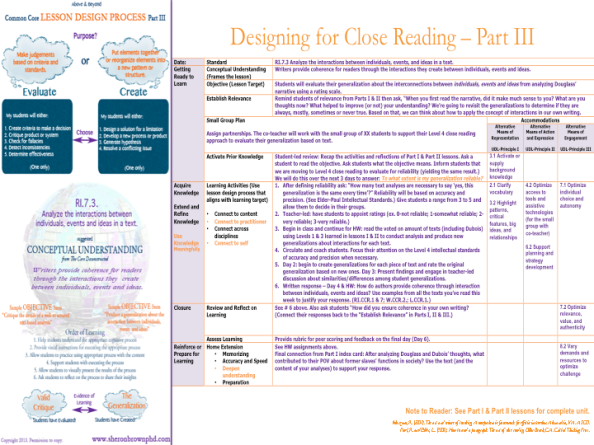

Part II–last week’s lesson–and Part III provide the mental structures required to engage with most types of TDQs. The lesson below assumes that the teacher would have scaffolded students’ interaction with complex text over the course of several readings as demonstrated in Parts I and II. Given that, the points to keep in mind as you review the lesson are the following:

- The standard of focus is RI.7.3. Analyze the interactions between individuals, events and ideas in a text.

- The lesson is based on the evaluate/create column for the conceptual and procedural knowledge components of the standard. (See The Core Deconstructed.)

- The lesson is designed for the authentic use of knowledge deeply understood in Part II through the process of evaluating.

- The Critical Thinking Foundation’s model for close reading is employed (Level 4)

- The Lesson Design Framework housing the lesson organizes the elements of an effective lesson.

So without further ado, here is Designing for Close Reading – Part III:

Close reading and TDQs: get clear on the definitions before you start conversing and planning in order to reduce teacher obscurity and increase student success.

The Aspen Institute (2012). Text Dependent Questions and the CCSS. Retrieved from http://kvecelatln.weebly.com/uploads/1/3/6/6/13660466/text_dep_qu_and_the_ccss.pdf

LiLaaC: Literacy, Language, and Culture